Teaching Nick Hornby’s About a Boy through Text-to-Self Analysis

A five-week case study at Samara State University 2014-2015

Nick Hornby’s classic coming-of-age tale About a Boy is a crucial part of Samara State University’s first year English curriculum. It has been used with first year International Relations students as well as students of the Philology department for many years. It is one of the most numerously supplied books in the Samara State University Philological Library and continues to be an English instructor’s first choice for Home Reading. Many of the educators at Samara State University are well versed in British literature – many have even written their respective theses on various contemporary and classical British literature topics. The lighthearted and delightful About a Boy is often a gateway text, a jumping-in point into other British texts as the language approachable for any immediate to advanced English Language Learner.

Hornby’s prestige as a celebrated contemporary British writer and the novel’s international following, coupled with an award-winning film adaptation makes it a great novel to study in Russian universities. Not very many texts are able to give Russian students an accurate glimpse of contemporary British society, typical British humor, literary style and provide a heartfelt story all in one package. Additionally, the novel an approved part of the literary canon that the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation upholds. The ministry along with Samara State University has produced an accompanying textbook that provides the curriculum for About a Boy. Instructors frequently use this accompanying textbook to teach About a Boy (Kozhukhova).

About a Boy centers in around middle aged Will Freeman and his unexpected friendship with schoolboy Marcus Brewer. In typical British wit, the novel is sarcastic, dialogue-driven and with large emphasis on character development. They meet in a snafu and after a series of awkward, though honest, encounters, the two find themselves friends and help each other in more ways than they can imagine. Throw in a suicidal mother, rock music, entertainment and culture references, school bullies, and a few sassy new friends and you have About a Boy. It’s a coming-of-age tale like any other. The pages are lined with realistic British themes such as divorce, support groups, single parenting, being a “hippie” as well as resentment-filled family gatherings.

The activities provided in the required textbook rely mostly on phonics and pronunciation, with a focus on vocabulary. All content divided by chapters. The chapters are organized by sections, with about three chapters in a section. This makes assigning tasks in preparation for the following week very simple. Working knowledge of the International Phonetic Alphabet is required in using the textbook. Instructors typically teach the British pronunciation of words. Students are expected to transcribe and then produce selected vocabulary words in IPA. It’s typical to have the students decode words as a homework assignment and have them write them on the board during the class period. In usual Russian university fashion, the text also provides ideas for many topic-driven presentations. “Google additional information on the following. Make a report or a presentation on the chosen topic” (Kozhukhova , 9) is an exercise found in the very first section.

There are also many excerpts of text from About a Boy that students are asked to translate into Russian. There are reading comprehension questions for every chapter. In every section there are also a few exercises asking students to locate a particular irregular verb and to give several forms of said verb (Kozhukhova, 17). As far as literature guides go – the textbook is thorough in terms of word-for-word comprehension. It does a thorough job scrutinizing individual words and grammar concepts within the novel. Almost every colloquial British English term is dissected and carefully analyzed for meaning. However, in terms of overall theme, the text falls short and is not able to provide Russian students any chance to make text-to-self connections. Russian students are to understand the story event-by-event, rather than overall lesson or moral of the story. Students are also never asked any higher-level thinking questions regarding tropes or themes. Moreover, students are not presented with the opportunity to discuss and reflect.

My intention was for Russian students to interact with the text using a Communicative Learning Approach (Richards) but also help them connect to the characters and themes present in About a Boyin a meaningful way. I implemented the Communicative Learning Approach through a text-based syllabus, requiring students to analyze the novel in different settings. I came up with a series of activities to help mediate discussions. While never focusing on grammar or vocabulary directly, my “mixed syllabus… integrate[d] reading, writing, and oral communication, and… t[aught] grammar through the mastery of texts rather than in isolation” (Richards, 37) – in line with the Communicative Learning Approach. My activities were designed to foster academic-level thinking through real-life interactions with About a Boy. I wanted students to construct meaning for themselves, and to act only as a conversation facilitator.

To completely write off the state mandated text would be erroneous, as the textbook provided necessary context in terms of requiring students to look up “Bob Marley” and other various culturally embedded terms as they appeared in the novel. One assignment asks students to Google additional information on the popular game Squash and the neighborhood known as Soho (Kozhukhova, 21). These concepts were not the focus of the story as they were only mentioned in passing, though requiring students to understand the cultural importance of Regent’s Park, Joni Mitchell or the restaurant Planet Hollywood, for example, are some things that were not reasonable to devote class time to. The textbook accomplished much in that regard. When I jumped in to instruct the students mid-semester and therefore, mid-novel, the tedious yet necessary tasks from the textbook had already proved useful in the basic informing of British or popular culture that is outside of Russia. Students were used to Googling concepts and bringing internet sources to report back the classroom. Under the instruction of the previous teacher, many of them placed a higher value on the topic presentations than the weekly novel reading assignments itself. So much emphasis was placed on giving a presentation on Bob Marley or said cultural reference, that the context in which it was mentioned was almost always lost.

The subjects of my study and five-week teaching experiment were first year students in the International Relations department during the fall semester of 2014. Most of their English levels were intermediate, though there were a few beginners within the group. The group consisted of fifteen students, almost every single student, with the exception of one or two, present at every meeting. The students were all female, with the exception of two. The two males were the main causes of any inconsistent attendance. A senior English instructor taught them for about four class periods prior to my takeover, and after the five weeks a different senior English instructor took over the class. The other two English instructors are native Russian speakers, though fluent in English. They have a combined more than forty years of teaching English under their belt. The course met Friday mornings for an hour-and-a-half at 8 AM in the Samara State University Main Campus and our last meeting was in the Samara State Interuniversity Museum of Humanities for a film showing. Although my stint was only for five-weeks, the observations and results are notable. Students truly did interact with the text in a remarkable way and were left for the second instructor with a better cultural and contextual understanding of About a Boy.

Week 1: Who…? Game

Notorious in schools across the United States is the Who…? Game. It is a popular icebreaker used by teachers with students of all ages, commonly found in a university setting. Teachers usually arrange a Bingo board and each square proposes a different question. The questions are generally random and are to stimulate talk amongst a new community. It is not uncommon to encounter this activity on the first meeting of the semester and to expect it several more times throughout one’s life. American students generally look forward to such an activity and find it interesting to have so-called small talk with one another. While an extremely contrived and artificial interaction, the activity is seldom met with gloom. The questions range from “Who has a dog?” to “Who likes ice cream?” to more rare inquiries such as “Who has two brothers?” The point is to get students out of their seats, walking around the room, asking other students if each question is true for them, and to write down an individual’s name if they indeed, do have a dog. The point is to talk to as many people as possible, not write anyone’s name more than once, find unique qualities of each person and to hopefully make a “bingo” – successfully complete a row of filled boxes on the Bingo board. The game ends when a student has completed the entire board or when the teacher decides to move on. The game is usually followed by a group discussion and often, formal introductions of a particular student to the class. It is a very popular ESL teaching tool.

I know that typically, groups within the Russian university are very tightly knit. Students have been studying alongside one another for semesters. Even the largest Russian universities, Samara State being one of them, have students go through their four or five year program in the same group, with very little opportunity to take courses independent from one another. Although I taught this game to first year students, they were already one another’s best friends, often found joking around and therefore already knew much about each other. I altered the game to fit the subject of About a Boy. On the board, I wrote questions such as “Who likes Nirvana?”, “Who has divorced parents?” and “Who has two best friends?” in order to gage textual comprehension (Appendix A). Those answers were simple and if a student had read the assigned chapters for homework or at least some kind of summary, it was a no-brainer. “Who has a favorite pair of shoes?” and “Who is good at math?” were among other simple questions. Students were to write down the answer for each characteristic on their own paper first, before we went down the list verbally, hence the numbering (Appendix A). If you had understood the most basic plot points, it would not have been difficult. There were more complicated questions such as “Who thinks life is unfair?” and “Who is an outcast?”, hoping to foster some sort of debate. Indeed, it did, as well as mutual agreement about the answers in the end, so the result of the game as a gage for reading comprehension proved to be successful. Questions that dealt more with emotions or personality required a deeper level of thinking than the factual type questions, but the students excelled in this level of thinking as well. I was not able to perform individual analyses but the overall positive reaction to the activity proved to me that it was successful. Students who were perhaps weaker readers or were not able to catch those facts during individual reading were hopefully able to learn from their classmates. I did not conduct the activity in the form of a Bingo board, but rather, a communicative activity that was dialogue driven. I wrote all the questions on the board in the front of the classroom (Appendix A) and students were welcome to shout out answers. Most of them did it in unison, showing me that as a whole, they came to class with a good foundation in understanding what they had read. Also, there were no instances of one student having to translate for the rest of their classmates – a situation I am presented with frequently within the Russian English-learning classroom. Whenever a characteristic fit more than one character from the novel, they were also quick to agree.

Lastly, we turned the activity into a class discussion about ourselves. It went from a discussion about Marcus being good at math to Marcus not liking football to who among the students was good at math or did not like football. Students raised their hands when I asked them these questions. The students reacted again, positively and to my surprise, gave opposing answers. They liked looking around and getting a laugh out of unexpected answers. Students that garnered attention immediately felt as if they had to explain their stance, without my prompting. That showed me that they understood the activity and were able to connect to it personally, rather than as a unit, as previous experiences within the Russian university has taught me. The class was often divided directly in half. Outliers were asked why they voted a particular way. They even engaged in pure English discussion without being prompted. Students thought it was hilarious to comment on their own dating mishaps or talk about their troubles making friends in a social setting. Students also had a laugh in finding out who really had a different hair color than what was natural. The segment about “Who I trying to find a boyfriend?” and “Who has many exes?” proved to be hilarious as well.

What was the purpose of the Who…? Game? It was to “explore futures of the general cultural context in which the text type is used and the social purposes the text type achieves” (Richards, 39). Incorporating Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (Cummins) in discussing literary content, in this first experiment, proved to be effective. Doors were opened in terms of students finally beginning to see the worth in studying such characters. Characters and their quirks were discussed in a manner that related to them personally for the very first time in their study of About a Boy. Talking about oneself in relation to an academic context is one way deliberately fostering text-to-self environments is crucial for understanding.

Week 2: 20 Questions Game

After a successful activity involving character and character traits, I used another activity to again, foster natural class discussion. My goal as an ESL instructor is for students to communicate openly and freely in English. About a Boy was merely a useful vehicle and I couldn’t wait to see if students could again, engage with the characters in a text in another meaningful way. This time, I had students come up to the front of the classroom one by one, turn to their classmates, while I wrote the name of a character on the board behind them. All their classmates knew which name I wrote and the student in the front had to ask questions about the name behind them. “Am I a boy?” “Am I old?” “Do I live in Cambridge?” “Do I have children?” were some questions asked. Although About a Boy has only three main characters, it has a multitude of secondary characters, which I drew upon to make this game more challenging.

This game’s design was to further foster a communicative competence. Students were encouraged to “maintain communication despite having limitations in one’s language knowledge” (Richards, 3). This is a one of the main aims of the Communicative Learning Approach in ESL instruction, accomplished through this lighthearted game. The student in the front was limited to their own vocabulary, though encouraged to expand on their working knowledge of English through prior knowledge about the text. The structure for such an activity was not strictly upheld; students were free to admit embarrassment or that they were stumped. There was no formal hand-raising or production of some sort of work. It took the form as a casual, lighthearted conversation. This fostered even more natural communication – confusion, frustration, and hilarity, followed by the euphoric moment in which they finally figured it out. What was most important in this activity was that they continually activated their prior knowledge and relied on communicating in English.

Week 3: “I am most like…” Introduction to Academic Writing

Due to a recent academic reform in higher education in Russia, universities are now seeking to instruct bachelor-degree seeking students on academic writing. One of President Vladimir Putin’s education initiatives is to get as many Russian universities in the Top 100. Russia seeks to have at least five of its own universities listed in the New York Times Higher Education’s Top 100 Universities by year 2020. Universities all around Russia, including Samara State are fiercely and competitively “seeking to modernize higher education” (Rankin), and accomplishing that requires mastery of academic writing in order to compete with Western universities (Fedorov). These first year International Relations students did not have a strong foundation in the basics of Academic English, so a small writing assignment helped them begin thinking about structured writing.

I realized that the students in this class did not know about introductory paragraphs or concluding paragraphs. They had not mastered the basics of essay writing still, and the English writing they had produced had remnants of Russian composition strategies. For example, run-on sentences continued to be an issue, as with the rote listing of facts. Writing appeared to be more a stream of consciousness than follow any structure. Facts were not cited and there was much confusion on how exactly they were to be woven throughout the text. First sentences were never “introductory” sentences but rather just the first in a series.

Through viewing past writing samples and hearing their presentations, I was able to come to this conclusion. So prior to beginning the text-to-self connection paragraph activity, I engaged students in a discussion about the characters. Prewriting is an invaluable skills taught in American schools, often accompanied by the use of Flow Charts or fill-in-the-blank Mind Maps. I asked them to list aspects of both Will and Marcus, and to finally compare them to one another. The students were divided into two groups. One group was to simply write down as many facts as they could about Marcus, while the other group wrote down as many facts as they could about Will. Every student had access to their novel and also the internet. Twenty minutes was spent discussing, sharing, appointing a “writer” and collaborating a list. They made the list on their own paper and collaborated with each other in creating the list. Then, a representative from each group came up to fill out a Venn Diagram that I had previously drawn on the board. Students said they had never seen such a chart, but understood immediately that each side was designated to a single character (Appendix B). After all the aspects had been discussed in a casual manner, and paraphrased on the board, then I engaged students in a deeper discussion – now that we know things about each of the character individually – what can we say about their similarities? Students discussed this topic with ease, as well. This time, I was the “writer” and imitated their manner of communicative learning. Students called out, collaborated and I didn’t say anything – just wrote it all down. It was a great introductory activity to the Text-to-self writing assignment that was to come.

It’s important to mention that throughout this group listing activity and while students were helping one another dictate the facts onto the board, students were never reprimanded for pronouncing something incorrectly or using the wrong grammar structure. That is never my aim in language instruction. If something was wrong and written on the board incorrectly, I left students to fix those mistakes themselves (Appendix B). If they didn’t catch the mistake, then it was just left there as it was. As a language teacher, I focus more on making students feel comfortable and free to speak. Students are the best critics of their own speech. Grammar, spelling and phonetics are secondary. I felt as if the novel About a Boy had enough references to proper constructions that class time should be devoted to simply using English in a natural setting. As long as they were communicating in English and not using any Russian, it accomplished my Communicative Learning goal. Were they using each other for help? Was their exchange and the topic of the exchange natural? Was prior knowledge activated and the strengths of individual students shared in order to strengthen the knowledge of the group’s? If so, the activity had worked.

I hoped to teach them basic paragraph structure while still incorporating aspects of text-to-self analysis into their assignment. First, I had students chose a character they personally related most to and explain to me verbally while they picked this particular character. Then, I gave them verbal examples of their essay topic and helped them understand that there was a structure that had to be followed. My Think-Aloud took this structure and continued every five minutes after the students began officially writing. I used my fingers as a physical numbering mechanism.

Which character are you more similar to? I think I’m really similar to Will because I like to do my own thing. Oh, I also like to spend the whole day watching TV! I also don’t like being bothered by children.

Students began writing almost immediately and were mostly divided 50-50 on Marcus/Will. The Venn Diagram was left on the board for reference. Then, they were to select three reasons why they personally connected to that character and to explain in further detail why. I also gave a concrete sentence starter for students to use. “I am most like… because…” It was repeated multiple times throughout the lesson for clarity. Students were to have an introductory sentence, three “body” sentences and a concluding sentence that said something new or profound about the paragraph they had just written. The three body sentences were to be made of three reasons why they were similar, along with a supporting detail. Three reasons were to become three body sentences.

One girl in the class thought that she related to Suzy (Marcus’s mother’s best friend). She had the most unique answer but still, was able to come up with a multitude of reasons. It seemed to be in mostly every student’s Zone of Proximal Development and met them at the level which they were at. Some students used their phones as translators for a word at a time, but nobody completely plugged their essay into a translating application. This was a success and inspiring to see. Students spent about twenty-five minutes constructing their essays.

Unfortunately, one girl in the class repeatedly wrote the essay as a bullet-pointed list. I gave her the opportunity to do it again, telling her simply to remove the numbering and put it in a cohesive paragraph, but during the next class period she turned in the exact same thing. She also proceeded to e-mail me the same thing (Appendix C). I did not accept her work and even after her peers continually explained the instructions to her, did she still not understand the assignment. Differentiation typically would have been adapted into the curriculum for this student, but due to the strictness and no-exceptions requirements in writing a basic academic paragraph, I would not allow her to turn it in. In this situation, I feel that language was a barrier, and not the assignment comprehension. Academic Writing may be best taught to Russians in their native language, especially regarding the fundamentals. However, despite that one assignment, I received stellar paragraphs that followed the “I am most like…” format complete with supporting facts from practically every student. Most students only wrote “I am most like…” in their introductory sentence and introductory sentence only; a few used that phrase in the two body sentences as well, though it was not difficult to redirect them.

Prior to this activity, I found that the questions the About a Boy state mandated text did not provide much context within the students’ lives. Many students did not see the point of reading About a Boy, as they did not have a thorough understanding of London nor the time period which the novel took place. Additionally, students often commented on the absurdity of the situation, i.e. a middle aged man and a young boy’s often overbearing relationship, rather than the themes and questions that such a relationship generated. This lack of context was furthered by their confusion at the duck scene and lack of understanding of Marcus’ mother’s numerous attempts to “top herself” (Hornby). Hornby never specifically states that it meat suicide, which was a source of great confusion for the students. They repeatedly used the term “top herself” as Hornby had done numerous times, but still lacked the actual, concrete understanding of that phrase. The lack of the novels’ context in contemporary Russian society made studying About a Boy fruitless at times. Rather than forcing students to understand and hopefully find humorous various key scenes in the novel, I wanted students to focus on making text-to-self connections.Students were not to spend so much time obsessing why a character would find himself in such an absurd situation as killing a duck, but rather, that there were relatable aspects of every character that they could associate themselves with.

Week 4: Project – Themes

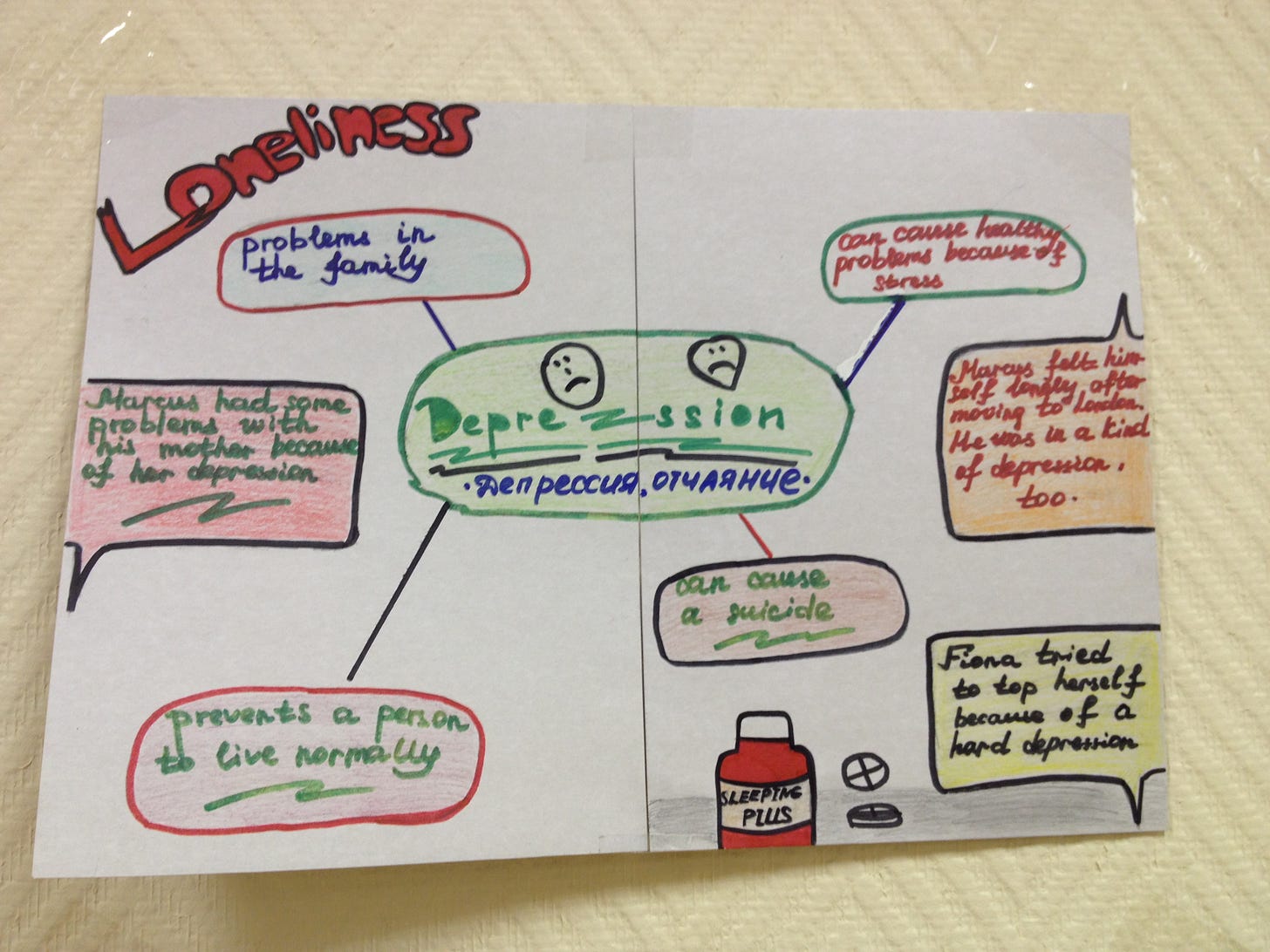

My hope was that in providing so much character analysis prior to the Themes Project, students were then able to make their own assumptions about the novel as a whole. The Themes Project also provided something that Russian students are not often given the opportunity to do – poster projects. It is not common in a Russian university to make an informative poster. Students are also not commonly graded using a rubric. I was about to introduce many of these new concepts to them in one project. I had come up with a list of themes that related to the novel. Mentorship, divorce, lying, worldly luxury – these were some of the themes that I had provided. Then, I wrote them all on the board and went down the list, asking students to name instances of said theme in the novel. Students were able to answer and reply with examples from the book, which showed me that even though coming up with themes is a learnt skill that I had not yet taught, identifying concrete examples of a broader theme is well within their reach. After we were able to name examples of each theme, I showed them an example project (Appendix D). My example was colorful, done with markers and elementary-looking to show the students that it didn’t have to be a professional production nor require any art skill. I chose the theme “mentorship” and gave the word in Russian underneath it. It was to be the biggest word on the poster, after all, identifying the main theme each student’s poster is to be focused on. Students were to give facts regarding the theme in the book and then facts regarding the theme in real life. In my example of mentorship, I wrote that “Will was forced into the mentorship position by both Marcus and his mother” and that “Marcus was mentored by Will”. In reference to “real life” I wrote that “[Mentorship] can be formal or informal,” “Mentors can give you advice on life, school, major decisions and even in relationships” and lastly, “it’s important for young people to have mentors, especially if they are outcasts or do not have many parental figures in their life”. These real life examples were purposefully similar to the theme regarding the actual characters in the book, hoping that students could draw on that fact and associate their own theme to real life with greater ease. The theme of mentorship was also not assigned to any student.

Another part of the project was to include three pictures of objects related to the theme. I left my drawings simple, giving students the choice to draw elementary ones like I did, or to use images from a computer. On the example poster, I drew the band symbol of Nirvana, a frame with two boys, portraying presumably Marcus and Will, and Nike shoes, as a main point of conflict for the characters in the novel involved Nike shoes. Students were encouraged to make their symbols as literal as the Nirvana or shoe, or a picture to represent an idea – depicted by the photo of Will and Marcus. After all, in the story the two were never photographed together. In my example poster, but lacking from my rubric are two quotes from the book. I included “’Marcus seems to think he needs adult male company. A father figure.’ pg. 126” and “’…for the first time, Will saw the kind of help that Marcus needed. Fiona had given him the idea that Marcus was after a father figure… Marcus needed help to be a kid, not an adult’ pg. 147” (Hornby). I was curious to see if students would be able to find relevance in quotes from the novel and emulate that on their own posters. However, I left it open ended. Students had one week to complete the assignment, were to bring them to the next meeting and be prepared to discuss them.

Themes that were divvied up included hardships in parenting, single parenting, divorce, depression, social norms, lying, parental control, worldly luxury, confidence, unexpected friendships, and individualism. I was surprised that such themes like individualism and social norms, the ones that seemed the most difficult to concretely identify within the novel, were the first to be chosen and the less abstract themes such as lying and worldly luxury were among the last to be chosen. The list, along with the instructions, rubric and a photo of the example poster was e-mailed to every student (Appendix E & F).

In the classes that I have observed in Samara State University, a majority of English presentations involve reading off a sheet of paper, content directly copied and pasted from Wikipedia. There is a lack of emphasis on peer understanding and response. A dialogue is not usually generated as a result of the presentation. Multimedia is seldom used, but when it is, the result is about the same. There is no attempt to incorporate formal presentation skills such as maintaining eye content or having an aesthetic quality. It seems as if the entire definition of the word “presentation” differs by each country, though presentations in Russia are not at fault. They are seen as a norm in the classroom. They provide a way for everyone to be graded fairly. Students all do the same amount of work. They understand the requirements and how to meet them.

With this brand new format and entirely new expectations for presentation, the experiment could have been a disaster. Without guidance and teacher mediation, the group discussion could have quickly gone awry. However, with the expectations set early on, the day of presentations went smoothly. Students volunteered one at a time to share their poster. I had modeled talking without a script with my own poster prior to the project being assigned and had expected the same. The students did not disappoint. Since it was obvious that they had spent so much time on their posters the week before, many were able to speak without reading directly off their poster. It was indeed a success in terms of presentation skills. They made eye contact with me and with the other students. They used the words and images on their poster as a point of reference. It seemed as if they were radiating with pride for their work. Posters were very aesthetically pleasing and reflected much more effort than any typical student in the United States would have produced, in my opinion, though perhaps not as professional-looking (Appendix G).

One thing that struck out to me was that not only were students excited about the project, they were willing to engage in conversation about their work too. Perhaps it had much to do with the group’s bond with one another. After each student presented their poster and explained the pictures they drew or the quotes that they chose, they were to ask their classmates if they had any questions. Classmates were encouraged to form questions while listening. Many students also provided quotes, though it was not required on the rubric. Their ability to find and include them on the poster showed me that they were truly engaging with the text at home and in a way that they could understand it enough to connect it to a broader theme. Students also emulated my Flow Chart format, though the rubric did not say anything about requiring students to organize information such a way. It was very interesting to see how students connected personally with the text. Text-to-text, text-to-self and text-to-world connections were ultimately made. I was one proud teacher.

Conversation ease echoes the sentiments that “permeable textual discussion occurs when students use their prior knowledge to make text-to-self, text-to-world, and text-to-text connections and share the knowledge gleans from those connections with peers and teachers to develop new learning” (Gritter, 445). A lot of thought was put into the image selection and I noticed a great emphasis on symbols students chose to use in their projects (Appendix G). Again, Russian students impressed me once again and reaffirmed that when they connect with a text, they do it in a meaningful, profound way.

Week 5: Watching the Film

As a celebration and the end of my five-week project, we watched the film together. When I first took over teaching the course, I was surprised to find out that a majority of students did not know it was a widely acclaimed film. Despite the cover having a picture of the two main characters, portrayed by Hollywood actors, they still did not know. So from the first class, there was a promise to eventually watch the film. Students banned together to find a classroom to host the viewing and also to get the file on a USB. They did most of the coordinating. They really came through in terms of initiating the idea and carrying it through. I was thoroughly impressed with their teamwork, ability to naturally divide tasks and also with their excitement to finally watch the film together. It was heartwarming and a joy to be a part of. The film had English subtitles at the bottom. During the film, posters were hung up and students were free to get up and read one another’s posters – a gallery walk. Since all the posters referenced the same novel, when students read one another’s posters and looked at the illustrations of their peers, they were able to deepen their understanding of the novel as a whole.

Conclusion

Teaching About a Boy, a text that is a norm for first year literature curriculum as well as a norm in the Russian university canon seemed daunting at first, but the experience was worthwhile. Text-to-self connections are phenomena I wish to see in future literature classrooms throughout Samara State University. It makes the literature come alive for students. Reading a particular novel does not merely have to be a rite of passage for first year students. It no longer has to be thought of in that way. It does not always require a lot of planning, as my five-week project proved – just a lot of Think Alouds and text modeling. Games teach more academic content than rote textbook activities, as I have found. Perhaps I was lucky enough to have worked with such a friendly and motivated group, but communicative learning techniques not only increased their communicative competence, but their confidence engaging in an academic discussion. Because of the informal engagement of both types of speech, student English speaking ability and listening comprehension increased drastically. At the end, students essentially led themselves and engaged in content discussion amongst themselves without needing a facilitator. My aim isn’t to be their teacher forever, but to instill aspects of communicative learning that they could carry with them to future topics. Students developed a familiarity for the text and felt kinship with certain characters. They saw themselves in Marcus or Will. They were able to viscerally put themselves in the same shoes as these fictional characters. They pictured living in the world that About a Boy created. They wanted to continue reading the novel, as reading the novel meant understanding themselves better, in a way. When Russian students make text-to-self connections in English language literature, it increases the chance that reading English becomes a lifelong activity.

Works Cited

Cummins, Jim. “Language Development and Academic Learning.” Multilingual Matters (1991); n. pag. Print.

Fedorov, Gleb. "Why Are Russia's Universities Struggling in International Ratings?" Russia Beyond The Headlines. N.p., 14 Oct. 2014. Web.

Gritter, Kristine. "Promoting Lively Literature Discussion." The Reading Teacher 64.6 (2011): 445-49. Web.

Hornby, Nick. About a Boy. New York: Riverhead, 1998. Print.

Kozhukhova, I. V., H. M. Ilichyeva, and O. B. Mekhyeda. About a Boy by Nick Hornby: Утверждено редакционно-избрательским цветом университет в качестве практикума для домашнего чтения. Samara: издательство «Самараский университет», 2012. Print.

Rankin, Jennifer. "Education Reform Inching Forward." The Moscow Times. N.p., 31 Aug. 2012. Web.

Richards, Jack. Communicative Language Teaching Today. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. Cambridge University Press. Web.

Appendix A – Who…? Game

Appendix B – Venn Diagram

Appendix C – Student Essay

The character I'm most similar to is Marcus.

1. For example: he always understands all things but can't explain his thoughts to other people. I can't sometimes explain my thoughts too.

2. For example: he is very friendly boy. In my opinion, he always try to make friends with unfamiliar people. So I very like to common with new people for me, find out their nature,interests and hobbies.

3. For example: he always is interested in all things around him. He like to reflect. And I like to reflect and complicate all simply things. I'm interested in all that around me. My friends say that I'm very curious.

In conclusion I think that I'm more similar with Marcus then other characters.

Appendix D – Teacher example of Themes Project

Appendix E – Written Instructions for Themes Project

First, you need to write the name of the theme very big. Themes are central topics in the book. They are ideas or motifs. Please translate the theme into Russian underneath the English word.

Then, you will need to write about the theme in reference to both the book and to real life. Talk about your theme in the book. Talk about your theme in real life. For example, I talked about mentorship and I discussed mentorship in the book and then mentorship in real life - what I think about it. You can include as many as you'd like. You can write them in bubbles like I did or in another, more creative, beautiful way.

Then, you will need two quotes from the book about your theme. They can be things that characters have said or things the narrator, Nick Hornby has said. Please put the page number.

Lastly, you will have two draw or print out three pictures related to the theme. They can be related to the book or related to the theme in real life. So for example, my theme was mentorship and I drew brand new Nike tennis shoes to represent the shoes that Will bought Marcus, a Nirvana smiley face to represent the time Will taught Marcus more about Kurt Kobain and how he wasn't really a football-er and also a framed portrait of Marcus and Will together. If you are not good at drawing, printing out photos from the internet is fine.

Appendix F – Rubric for Themes Project

Theme in English - 1

Theme translated into Russian - 1

Facts about the theme in the book - 5

Facts about the theme in real life - 5

Three pictures - 3

If you do all these things, you can get 15 points! Your grade will be marked down in class after you present them.

They are due in class on Friday. You can do them on a nice, giant paper like I did or on regular paper.

Appendix G – Gallery of Student Work “Themes Project”